Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistor (MOSFET): A Comprehensive Overview

The Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistor (MOSFET) is a cornerstone of modern electronics, enabling advancements in digital and analog circuits, power systems, and microprocessors. Invented in 1959 by Dawon Kahng and Martin Atalla at Bell Labs, MOSFETs revolutionized the semiconductor industry by offering superior efficiency, scalability, and integration compared to bipolar junction transistors (BJTs). Today, MOSFETs are ubiquitous in integrated circuits (ICs), power electronics, and wireless communication systems, forming the backbone of technologies from smartphones to electric vehicles.

Structure of a MOSFET

A MOSFET comprises three primary terminals—Gate, Source, and Drain—along with a fourth terminal, the Body or Substrate. Its layered structure includes:

Substrate: Typically made of silicon, doped as p-type (for n-channel MOSFETs) or n-type (for p-channel MOSFETs).

Oxide Layer: A thin insulating layer (historically silicon dioxide, SiO?) separating the gate from the substrate. Modern devices may use high-k dielectrics to reduce leakage.

Gate Electrode: Originally metal, now often polycrystalline silicon (polysilicon), which applies the electric field to control the channel.

Source/Drain Regions: Heavily doped regions (n? for n-channel, p? for p-channel) that facilitate carrier flow.

The channel forms between the source and drain when a sufficient gate voltage is applied, creating a conductive path.

Working Principle

MOSFET operation hinges on voltage-controlled channel formation:

Enhancement Mode:

n-channel: A positive gate voltage () attracts electrons, forming an inversion layer (n-type channel) in the p-substrate. Current flows from drain to source when is applied.

p-channel: A negative gate voltage () attracts holes, creating a p-type channel in the n-substrate.

Depletion Mode: Conducts at ; voltage applied to reduce conductivity.

Regions of Operation:

Cutoff: No channel; .

Triode/Linear: Channel forms; increases linearly with .

Saturation: Channel pinches off; stabilizes, controlled by .

Types of MOSFETs

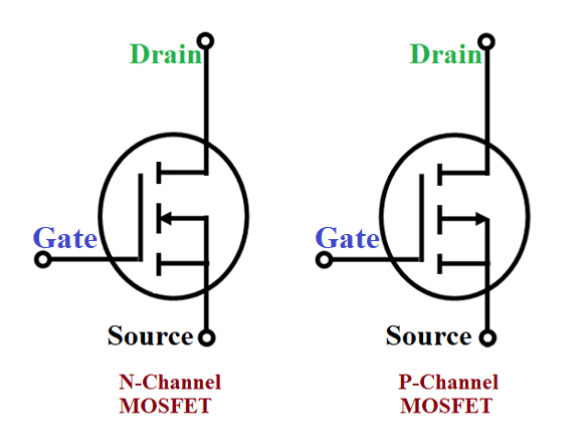

By Channel Type:

n-channel (NMOS): Faster due to electron mobility.

p-channel (PMOS): Used alongside NMOS in CMOS technology for low power consumption.

By Operation Mode:

Enhancement MOSFET: Normally off; requires gate voltage to conduct. Dominant in digital circuits.

Depletion MOSFET: Normally on; requires voltage to turn off.

By Structure:

Planar MOSFET: Traditional 2D design.

FinFET: 3D fin structure for better gate control, reducing leakage in sub-22nm technologies.

Power MOSFET: Vertical structures (e.g., VDMOS, Trench MOSFET) for high voltage/current handling.

Applications

Digital Circuits: MOSFETs form logic gates, memory cells, and microprocessors. CMOS technology pairs NMOS and PMOS for minimal static power use.

Analog Circuits: Amplifiers, oscillators, and data converters leverage MOSFETs' high input impedance.

Power Electronics: Switched-mode power supplies, motor drives, and inverters use power MOSFETs for efficient switching.

RF Systems: High-frequency MOSFETs enable wireless communication and radar systems.

Advantages

High Input Impedance: Minimal gate current reduces power loss.

Fast Switching: Ideal for high-frequency applications.

Scalability: Continuous miniaturization supports Moore’s Law.

Thermal Stability: Less prone to thermal runaway than BJTs.

Challenges

Leakage Currents: Ultra-thin oxides (sub-2nm) suffer quantum tunneling, increasing power dissipation.

Reliability Issues: Hot carrier injection and gate oxide breakdown degrade performance over time.

Fabrication Complexity: Short-channel effects (e.g., drain-induced barrier lowering) complicate sub-10nm designs.

Thermal Management: Power MOSFETs require heat sinks to manage joule heating.

Future Directions

Innovations like gallium nitride (GaN) and silicon carbide (SiC) MOSFETs address high-power and high-temperature needs. Gate-all-around (GAA) transistors and 2D material-based devices (e.g., graphene) promise further scaling.

Conclusion

MOSFETs underpin the digital age, enabling compact, energy-efficient electronics. As technology advances, they continue to evolve, overcoming physical limits through novel materials and architectures. Their enduring relevance ensures MOSFETs will remain pivotal in shaping future electronic systems.

Kevin Chen

Founder / Writer at Rantle East Electronic Trading Co.,Limited

I am Kevin Chen, I graduated from University of Electronic Science and Technology of China in 2000. I am an electrical and electronic engineer with 23 years of experience, in charge of writting content for ICRFQ. I am willing use my experiences to create reliable and necessary electronic information to help our readers. We welcome readers to engage with us on various topics related to electronics such as IC chips, Diode, Transistor, Module, Relay, opticalcoupler, Connectors etc. Please feel free to share your thoughts and questions on these subjects with us. We look forward to hearing from you!

Start With

Start With Include With

Include With